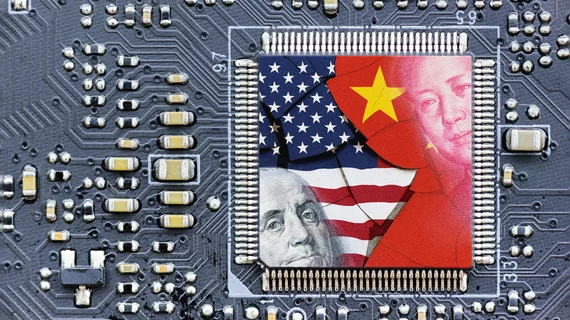

Race for AI dominance: 5 points to ponder about US v. China

AI that’s intended to let cars drive themselves can be repurposed to let tanks level cities. And AI can just as easily weaponize a virus as diagnose it. These are not secrets. However, the boundaries between the “safely civilian” and the “militarily destructive” are “inherently blurred.” That’s largely why the U.S. has clamped down on exports of advanced semiconductors to China.

The observation is from the political scientist Ian Bremmer and the serial tech entrepreneur Mustafa Suleyman. The unlikely pair has authored an essay asking whether governments of tech-forward nations can summon the will to effectively bridle AI “before it’s too late.” Foreign Affairs published the piece online Aug. 16.

A recurring touchpoint in the article is the clash between the world’s top two AI titans. Here are five excerpts from those portions.

1. China and the United States both view AI development as a zero-sum game.

“From the vantage point of Washington and Beijing, the risk that the other side will gain an edge in AI is greater than any theoretical risk the technology might pose to society or to their own domestic political authority. … In their view, a ‘pause’ in development to assess risks, as some AI industry leaders have called for, would amount to foolish unilateral disarmament.”

2. With hooks deeply set in its ostensibly ‘free market’ companies, the Chinese Communist Party probably could rein in AI within its borders if it really wanted to.

Alas, it probably doesn’t really want to—and reciprocating total control would be difficult to pull off in the West anyway. “Because [private enterprises] jealously guard their computing power and algorithms, they alone understand (most of) what they are creating and (most of) what those creations can do,” Bremmer and Suleyman point out. “A few big firms may retain their advantage—or they may be eclipsed by smaller players as low barriers to entry, open-source development and near-zero marginal costs lead to uncontrolled proliferation of AI.”

3. AI-aided control of nuclear arms is probably a fanciful thought experiment.

“AI systems are infinitely easier to develop, steal and copy than nuclear weapons. As the new generation of AI models diffuses faster than ever, the nuclear comparison looks ever more out of date. Even if governments can control access to the materials needed to build the most advanced models, they can do little to stop the proliferation of those models once they are trained and therefore require far fewer chips to operate.”

4. The rest of the world could help manage tensions between the two AI superpowers.

In the process, other nations might thwart advanced AI systems from multiplying and running amok. “One area where Washington and Beijing may find it advantageous to work together is in slowing the proliferation of powerful systems that could imperil the authority of nation-states. At the extreme, the threat of uncontrolled, self-replicating artificial general intelligence (AGI) models—should they be invented in the years to come—would provide strong incentives to coordinate on safety and containment.”

5. Some level of online censorship is going to be necessary.

For that task, the world will need some sort of “geotechnology stability board,” Bremmer and Suleyman suggest. “If someone uploads an extremely dangerous model, this [international] body must have the clear authority—and ability—to take it down or direct national authorities to do so,” they add. “This is another area for potential bilateral cooperation.”

There’s more. Read the rest.